The Geometry of War: Modeling the Primarch Duel with Newtonian Physics and Stochastic Control

Published:

The jetbike screams through the void, its engine a thunderclap in the silence of space. At the controls, Jaghatai Khan—the Warhawk, Primarch of the White Scars—pushes his mount to the absolute limit. Ahead, wreathed in toxic mist, stands his corrupted brother Mortarion, the Death Lord of Nurgle. The distance between them is measured not in meters, but in heartbeats. One hundred meters. Fifty. Twenty. The Khan’s velocity meter reads 35 m/s, climbing. His stamina gauge flickers—red, yellow, green—as he burns through his reserves. The toxic aura of the Lantern’s Glow sears his armor, his health bleeding away with every meter closer.

This is not a story. This is a Stochastic Optimal Control Problem.

The legendary duel at the Lion’s Gate Spaceport represents one of the most mathematically elegant combat scenarios in science fiction: a one-dimensional pursuit where victory depends on balancing three competing objectives—Speed (for damage), Distance (to avoid toxicity), and Endurance (stamina management)—all while navigating random interventions from the Warp itself. The Khan must solve, in real-time, a constrained optimization problem where the constraints are stochastic, the objective function is non-convex, and failure means death.

This post presents a technical walkthrough of the WARHAWK_STOCHASTIC project, a high-fidelity physics simulation that models this duel using Advanced Newtonian Dynamics, Runge-Kutta 4th Order Integration, and PID Control Theory. We will derive the physics from first principles, implement stochastic differential equations for Warp interventions, and perform Monte Carlo analysis to quantify the probability of victory under different strategies.

Historical Context:

The mathematical modeling of combat has a rich history, from Lanchester’s square law (1916) to modern game-theoretic approaches. However, most combat models treat participants as discrete agents with simple rules. The innovation here is treating combat as a continuous-time optimal control problem with stochastic disturbances—the same framework used in aerospace engineering for missile guidance and in finance for portfolio optimization.

The use of PID controllers for combat AI dates to early robotics, but applying them to a physics-based simulation with stochastic elements is novel. The combination of deterministic physics (Newton’s laws) with stochastic processes (Brownian motion, Poisson events) creates a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) system that requires careful numerical treatment.

The Warhammer 40K setting provides a perfect testbed because it imposes clear physical constraints (mass, thrust, drag) while introducing narrative elements (Warp interventions) that map naturally to stochastic processes. This is not just a game simulation—it’s a case study in stochastic optimal control with applications to autonomous vehicle path planning, drone combat systems, and even financial trading algorithms.

All figures and data discussed here were generated using the simulation engine committed to the repository. The code is open-source and fully reproducible—you can run every experiment yourself and verify these claims.

1. The Physics of Combat

To model this duel, we cannot treat the Khan as a simple point mass or use kinematic equations. We must model the full Newtonian dynamics with proper force balance, energy constraints, and biological decay. The system is a coupled set of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) that describe position, velocity, stamina, health, and toxic exposure.

The state vector is six-dimensional: \(\mathbf{x}(t) = [x(t), v(t), S(t), H(t), R(t), M(t)]^T\)

where:

- $x(t)$: Position (distance from Mortarion, in meters)

- $v(t)$: Velocity (m/s, negative when moving toward enemy)

- $S(t)$: Stamina (0-100, energy reserve)

- $H(t)$: Health (0-100, biological integrity)

- $R(t)$: Rot stacks (cumulative toxic exposure)

- $M(t)$: Mortarion’s health (0-25000)

The dynamics are governed by a system of coupled ODEs that we’ll derive step by step.

1.1 Newtonian Dynamics: Force Balance

The Khan’s jetbike obeys Newton’s second law: $\mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a}$. In one dimension, this becomes:

\[\dot{v} = \frac{F_{net}}{m}\]where $F_{net}$ is the sum of all forces acting on the bike. There are two primary forces:

Thrust Force ($F_{thrust}$): The jetbike engine provides controllable thrust in the range $[-F_{max}, F_{max}]$, where $F_{max} = 28,000$ N. Negative thrust means acceleration toward Mortarion (the enemy is at $x=0$).

Drag Force ($F_{drag}$): Air resistance opposes motion. At high speeds, drag is quadratic in velocity: \(F_{drag} = -C_d v |v|\)

The negative sign ensures drag always opposes motion. The absolute value $\mid v \mid$ ensures drag magnitude increases with speed regardless of direction. This is the standard quadratic drag model used in aerospace engineering.

Why Quadratic Drag?

At low speeds (laminar flow), drag is linear: $F_{drag} \propto v$. At high speeds (turbulent flow), drag is quadratic: $F_{drag} \propto v^2$. The Khan’s jetbike operates in the turbulent regime (Reynolds number $Re > 10^5$), so quadratic drag is physically accurate.

The net force is: \(F_{net} = F_{thrust} + F_{drag} = F_{thrust} - C_d v |v|\)

Therefore, the acceleration is: \(\dot{v} = \frac{F_{thrust} - C_d v |v|}{m}\)

With $m = 800$ kg (the Khan plus his power armor and bike) and $C_d = 1.0$ N·s²/m², this gives us the velocity dynamics.

Position Dynamics:

Position is simply the integral of velocity: \(\dot{x} = v\)

This completes the kinematic equations. But we’re not done—we need to model the constraints.

1.2 The Stamina Constraint: Energy Management

The Khan cannot maintain maximum thrust indefinitely. Every Newton-second of thrust costs stamina. This creates a resource management problem: use too much thrust early, and you’ll be exhausted when you need speed for a critical strike.

The stamina dynamics are: $$\dot{S} = \begin{cases} R_{recover} & \text{if } F_{thrust} = 0 \

- |F_{thrust}| \cdot C_{cost} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

where:

- $R_{recover} = 15$ stamina/second (recovery rate when coasting)

- $C_{cost} = 0.04$ stamina per Newton-second (thrust cost)

This is a linear energy model: stamina burns proportionally to thrust magnitude. When $S = 0$, the Khan cannot produce thrust ($F_{thrust} = 0$), effectively becoming a glider. In practice, this means death—without thrust, he cannot escape the toxic aura.

The Energy-Time Trade-off:

This creates a fundamental trade-off. To deal damage, the Khan needs high velocity (momentum = $mv$). But high velocity requires sustained high thrust, which depletes stamina. The optimal strategy must balance:

- Aggressive acceleration (high thrust) to build speed quickly

- Stamina conservation (low thrust) to maintain endurance

- Strategic timing (when to burn stamina for maximum damage)

This is a classic optimal control problem with state constraints: maximize damage dealt while ensuring $S(t) > 0$ for all $t$.

1.3 The Toxicity Field: Distance-Dependent Decay

Mortarion’s “Lantern’s Glow” is a toxic aura that decays biological matter. The closer you are, the faster you die. This is modeled as a distance-dependent health decay:

\[\dot{H} = -\left( \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 R(t) \right)\]where:

- $\alpha_0 = 0.5$ HP/second (base toxicity)

- $\alpha_1 = 0.1$ HP/second per rot stack (scaling factor)

- $R(t)$: Rot stacks (cumulative toxic exposure)

But wait—where does the distance dependence come in? It’s in the rot accumulation rate:

\[\dot{R} = \frac{\beta}{x(t) + \epsilon}\]where $\beta = 0.2$ rot/second and $\epsilon = 1$ m (prevents division by zero).

The Physics of Rot Accumulation:

This inverse-distance relationship models diffusion-limited exposure. The toxic particles have a finite diffusion rate. At distance $x$, the concentration is proportional to $1/x^2$ (inverse square law for a point source). The accumulation rate is proportional to concentration, so $\dot{R} \propto 1/x^2$. However, we use $1/x$ for computational simplicity and to match the problem statement.

The Feedback Loop:

This creates a dangerous feedback loop:

- Get closer to deal damage → Rot accumulates faster

- Rot accumulates → Health decays faster

- Health decays → Must retreat or die

- Retreat → Cannot deal damage

The optimal strategy must break this loop by minimizing time spent in the danger zone while maximizing damage per approach.

1.4 Momentum-Based Damage: Why Speed Matters

The Khan’s damage output is momentum-based. When he strikes (within 6 meters and moving toward Mortarion at $v < -4$ m/s), the damage is:

\[D = D_{base} + k_{momentum} \cdot mv + \text{critical bonuses}\]where:

- $D_{base} = 1100$ HP (base strike damage)

- $k_{momentum} = 0.03$ (momentum scaling factor)

- $m = 800$ kg (mass)

Critical bonuses: 2.5× for $\mid v \mid > 30$ m/s, 1.7× for $ v > 25$ m/s, 1.2× for $\mid v \mid > 20$ m/s

The Physics of Impact:

This models kinetic energy transfer. When the Khan strikes at velocity $v$, his kinetic energy is $KE = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$. The damage scales with momentum ($mv$) rather than energy ($mv^2$) because:

- Impulse transfer: Damage in combat is about force over time, not energy. Momentum ($mv$) directly relates to impulse ($F\Delta t = \Delta(mv)$).

- Practical scaling: Energy scaling ($v^2$) would make high-speed strikes unrealistically powerful. Momentum scaling ($v$) provides a more balanced progression.

Critical Hit Mechanics:

The critical hit bonuses model structural failure. At very high speeds ($>30$ m/s = 108 km/h), the impact doesn’t just transfer momentum—it causes catastrophic structural damage. This is analogous to the difference between a car crash at 50 km/h (survivable) and 150 km/h (fatal).

The Damage-Time Trade-off:

This creates another trade-off:

- High-speed strikes: Deal massive damage but require sustained acceleration (stamina cost)

- Low-speed strikes: Deal minimal damage but conserve stamina

The optimal strategy must find the sweet spot: fast enough for meaningful damage, but not so fast that stamina is exhausted before victory.

1.5 Mortarion’s Regeneration: The Race Against Time

Mortarion regenerates at a constant rate: \(\dot{M} = R_{regen} = 20 \text{ HP/second}\)

This means the Khan must deal damage faster than Mortarion can heal. If the Khan’s average damage rate is less than 20 HP/second, he will never win—Mortarion will outheal the damage.

The Damage Rate Calculation:

If the Khan strikes every $\Delta t$ seconds with average damage $\bar{D}$, his damage rate is: \(\text{Damage Rate} = \frac{\bar{D}}{\Delta t}\)

For victory, we need: \(\frac{\bar{D}}{\Delta t} > R_{regen} = 20 \text{ HP/s}\)

With $D_{base} = 1100$ and typical momentum bonus, $\bar{D} \approx 1500$ HP per strike. This requires: \(\Delta t < \frac{1500}{20} = 75 \text{ seconds}\)

The Khan must strike at least once every 75 seconds, on average, to outpace regeneration. But strikes require:

- Building speed (time cost)

- Approaching close range (exposure to toxicity)

- Recovering stamina between strikes (time cost)

The optimal strategy must balance these competing time costs.

2. Numerical Integration: Why RK4?

The system of ODEs we’ve derived is stiff—it has both fast dynamics (velocity changes rapidly during acceleration/braking) and slow dynamics (health decays gradually). Simple Euler integration would require extremely small time steps to remain stable, making the simulation computationally expensive.

The Stiffness Problem:

Consider the velocity equation: \(\dot{v} = \frac{F_{thrust} - C_d v |v|}{m}\)

At high speeds, the drag term $C_d v |v|$ dominates. If $v = 30$ m/s, drag is $C_d \cdot 30^2 = 900$ N. With $F_{max} = 28,000$ N, the net acceleration is: \(a = \frac{28,000 - 900}{800} = 33.9 \text{ m/s}^2\)

But if we’re braking ($F_{thrust} = 0$), acceleration is: \(a = \frac{0 - 900}{800} = -1.125 \text{ m/s}^2\)

The system can transition from $+33.9$ m/s² to $-1.125$ m/s² in a single timestep. This is a stiff system—the characteristic timescales vary by orders of magnitude.

Euler Integration Fails:

With Euler integration: \(v_{n+1} = v_n + \dot{v}_n \cdot \Delta t\)

For stability, we need $\Delta t < \frac{2}{\mid \lambda_{max} \mid}$ where $\lambda_{max}$ is the largest eigenvalue of the Jacobian. For our system, this requires $\Delta t < 0.01$ seconds, meaning 24,000 timesteps for a 240-second duel. This is computationally expensive.

Runge-Kutta 4th Order (RK4) to the Rescue:

RK4 is a four-stage explicit method that achieves 4th-order accuracy while remaining stable for moderately stiff systems. The method evaluates the derivative at four points and combines them:

\(k_1 = f(t_n, y_n)\) \(k_2 = f(t_n + \frac{\Delta t}{2}, y_n + \frac{\Delta t}{2}k_1)\) \(k_3 = f(t_n + \frac{\Delta t}{2}, y_n + \frac{\Delta t}{2}k_2)\) \(k_4 = f(t_n + \Delta t, y_n + \Delta t \cdot k_3)\) \(y_{n+1} = y_n + \frac{\Delta t}{6}(k_1 + 2k_2 + 2k_3 + k_4)\)

Why This Works:

RK4 has a larger stability region than Euler. For our system, RK4 remains stable with $\Delta t = 0.05$ seconds, requiring only 4,800 timesteps—a 5× reduction in computational cost.

Implementation Details:

Our implementation separates derivative computation from state updates:

def compute_derivatives(self, thrust_cmd):

"""Returns derivatives without modifying state."""

# Compute d_pos, d_vel, d_stamina, etc.

return {'d_pos': ..., 'd_vel': ..., ...}

def apply_derivatives(self, derivatives, dt):

"""Applies derivatives to update state."""

self.pos += derivatives['d_pos'] * dt

self.vel += derivatives['d_vel'] * dt

# ... etc

This separation is crucial for RK4, which needs to evaluate derivatives at intermediate states without corrupting the current state. During the RK4 stages, we temporarily modify state to compute $k_2$, $k_3$, $k_4$, then restore the original state before applying the final update.

The RK4 Step Function:

def rk4_step(state, thrust_cmd, dt):

# Save current state

pos0, vel0, ... = state.pos, state.vel, ...

# k1: derivative at current state

k1 = state.compute_derivatives(thrust_cmd)

# k2: derivative at midpoint using k1

state.pos = pos0 + 0.5 * k1['d_pos'] * dt

state.vel = vel0 + 0.5 * k1['d_vel'] * dt

# ... (temporarily modify state)

k2 = state.compute_derivatives(thrust_cmd)

# k3, k4: similar process

# ...

# Restore state and apply weighted combination

state.pos = pos0

state.vel = vel0

# ... (restore)

combined = {

'd_pos': (k1['d_pos'] + 2*k2['d_pos'] + 2*k3['d_pos'] + k4['d_pos']) / 6.0,

# ... (weighted average)

}

state.apply_derivatives(combined, dt)

This implementation ensures numerical stability and accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

3. Control Theory: PID Controllers and State Machines

The Khan’s AI uses Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers to manage each combat phase. PID control is the workhorse of industrial automation, used in everything from cruise control to drone stabilization. Here, we apply it to combat AI.

3.1 PID Controller Derivation

A PID controller computes a control signal $u(t)$ based on the error $e(t) = r(t) - y(t)$, where $r(t)$ is the setpoint (desired value) and $y(t)$ is the measured value:

\[u(t) = K_p e(t) + K_i \int_0^t e(\tau) d\tau + K_d \frac{de}{dt}\]The three terms serve different purposes:

Proportional ($K_p$): Provides immediate response to error. Large $K_p$ means aggressive correction, but can cause overshoot and oscillation.

Integral ($K_i$): Eliminates steady-state error. If there’s a persistent offset, the integral term accumulates and drives it to zero. However, integral windup can cause instability.

Derivative ($K_d$): Provides damping. It anticipates future error based on the rate of change, reducing overshoot and oscillation.

Discrete-Time Implementation:

In our simulation, we use a discrete-time approximation:

def compute(self, setpoint, measured, dt):

error = setpoint - measured

self.integral += error * dt # Trapezoidal rule

derivative = (error - self.prev_error) / dt # Backward difference

output = (self.kp * error) + (self.ki * self.integral) + (self.kd * derivative)

self.prev_error = error

return np.clip(output, self.min_out, self.max_out) # Saturation

Tuning Parameters:

Each combat phase requires different PID parameters:

- Approach Phase: $K_p=1500$, $K_i=8$, $K_d=400$ (moderate response, smooth acceleration)

- Strike Phase: $K_p=2500$, $K_i=15$, $K_d=600$ (aggressive, precise control)

- Retreat Phase: $K_p=1800$, $K_i=0$, $K_d=300$ (fast response, no integral to prevent windup)

- Recovery Phase: $K_p=1200$, $K_i=5$, $K_d=200$ (gentle, stable hovering)

These parameters were tuned through trial and error (Ziegler-Nichols method) to achieve desired response characteristics.

3.2 State Machine: Phase Transitions

The Khan’s AI uses a finite state machine with four states:

- APPROACH: Build speed and close distance to ~20 meters

- STRIKE: Maintain close range and maximize velocity for damage

- RETREAT: Escape to safe distance (>75 meters)

- RECOVER: Hover at ~85 meters, restore stamina and health

State Transition Logic:

if self.phase == "APPROACH":

if state.pos < 25.0: # Close enough to strike

self.phase = "STRIKE"

self.strike_pid.integral = 0 # Reset to prevent windup

elif self.phase == "STRIKE":

if state.pos <= 2.0 or state.stamina < 10.0: # Too close or exhausted

self.phase = "RETREAT"

elif self.phase == "RETREAT":

if state.pos > 75.0: # Safe distance reached

self.phase = "RECOVER"

elif self.phase == "RECOVER":

if state.stamina > 70.0 and state.health > 20.0: # Ready to fight

self.phase = "APPROACH"

Why State Machines Work:

State machines provide structured decision-making that’s easier to reason about than monolithic control logic. Each state has clear objectives and transition conditions, making the AI’s behavior predictable and tunable.

Hybrid Control Strategy:

The AI uses a hybrid approach: PID control for smooth phases (approach, recovery) and bang-bang control (maximum thrust) for aggressive phases (strike, retreat). This combines the precision of PID with the raw power of maximum thrust when needed.

4. Stochastic Elements: The Chaos of the Warp

The Warp introduces stochastic disturbances that make each duel unique. We model two types of randomness:

- Continuous noise: Brownian motion affecting velocity

- Discrete events: Poisson processes for Warp interventions

4.1 Brownian Motion: Continuous Velocity Noise

The Warp is chaotic. Wind, gravity fluctuations, and psychic disturbances create random forces. We model this as Brownian motion (Wiener process) added to velocity:

\[dv_{noise} = \sigma dW\]where:

- $\sigma = 5.0$ m/s (volatility parameter)

- $dW$: Wiener process increment (Gaussian white noise)

The Wiener Process:

A Wiener process $W(t)$ is a continuous-time stochastic process with:

- $W(0) = 0$

- $W(t) - W(s) \sim \mathcal{N}(0, t-s)$ for $t > s$ (independent increments)

- $W(t)$ has continuous paths (almost surely)

In discrete time, we approximate: \(dW \approx \Delta W = \mathcal{N}(0, \Delta t)\)

So: \(v_{noise} = \sigma \cdot \mathcal{N}(0, \sqrt{\Delta t}) = \sigma \cdot \sqrt{\Delta t} \cdot \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\)

Implementation:

dW = np.random.normal(0, np.sqrt(dt)) # Wiener increment

velocity_noise = NOISE_VOLATILITY * dW

state.vel += velocity_noise

This adds unpredictability to the simulation. The same strategy can lead to different outcomes due to random velocity fluctuations.

4.2 Poisson Events: Warp Interventions

The Warp occasionally intervenes with dramatic events:

- Nurgle’s Rot: Stuns the Khan, reduces velocity, damages health

- Emperor’s Grace: Restores stamina, cleanses rot, removes stun

These are modeled as Poisson processes with time-varying rates.

Poisson Process Basics:

A Poisson process $N(t)$ counts the number of events in $[0, t]$. The probability of exactly $k$ events is:

\[P(N(t) = k) = \frac{(\lambda t)^k e^{-\lambda t}}{k!}\]where $\lambda$ is the rate parameter (events per second).

For small time intervals $\Delta t$, the probability of exactly one event is: \(P(N(\Delta t) = 1) \approx \lambda \Delta t\)

Nurgle’s Rot:

The probability of Nurgle intervening increases with rot accumulation:

\[\lambda_{nurgle}(t) = \lambda_0 \cdot (1 + 0.05 \cdot R(t))\]where $\lambda_0 = 0.03$ events/second. This models the feedback loop: more rot → higher intervention probability → more rot.

Emperor’s Grace:

The Emperor’s intervention probability increases when the Khan is in critical condition:

\[\lambda_{emperor}(t) = \begin{cases} 2\lambda_0 & \text{if } H(t) < 30 \\ \lambda_0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]where $\lambda_0 = 0.02$ events/second. This models divine intervention when all seems lost.

Implementation:

nurgle_prob = PROB_NURGLE * (1 + (state.rot * 0.05)) * dt

if np.random.random() < nurgle_prob:

state.vel *= 0.1 # Momentum loss

state.set_stunned(duration=2.0)

state.health -= 5.0

return "NURGLE_RUST"

emp_prob = PROB_EMPEROR * dt

if state.health < 30:

emp_prob *= 2.0

if np.random.random() < emp_prob:

state.stamina = STAMINA_MAX

state.rot = max(0, state.rot - 10.0)

state.stunned = False

return "EMPEROR_LIGHT"

4.3 Stochastic Differential Equations Framework

The complete system is a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE):

\[d\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, u, t) dt + \mathbf{G}(\mathbf{x}, t) d\mathbf{W}\]where:

- $\mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, u, t)$: Drift term (deterministic dynamics)

- $\mathbf{G}(\mathbf{x}, t)$: Diffusion term (stochastic noise)

- $d\mathbf{W}$: Wiener process increments

For our system:

- Drift: Newtonian dynamics, stamina, health decay, rot accumulation

- Diffusion: Brownian motion in velocity

- Jump processes: Poisson events (Nurgle, Emperor)

This is a hybrid SDE with both continuous noise and discrete jumps—a challenging numerical problem that we solve by separating the deterministic integration (RK4) from the stochastic updates (applied after each RK4 step).

5. Software Architecture: Clean Separation of Concerns

The codebase is organized into modular components:

WARHAWK_STOCHASTIC/

├── src/

│ ├── core/

│ │ ├── dynamics.py # Physics engine (ODE system)

│ │ └── stochastic.py # Warp engine (SDE components)

│ ├── simulation/

│ │ ├── single_run.py # Single duel execution

│ │ ├── monte_carlo.py # Parallel Monte Carlo

│ │ └── strategy.py # PID controllers + state machine

│ ├── analysis/

│ │ └── outcome_clustering.py # K-means analysis

│ └── visualization/

│ ├── temporal_plots.py

│ ├── spatial_plots.py

│ └── probabilistic_plots.py

└── main.py # Entry point

State Management:

The AdvancedDuelState class encapsulates all state variables and provides clean interfaces:

compute_derivatives(): Returns derivatives without side effectsapply_derivatives(): Updates state from derivativescheck_strike(): Discrete event detection

This separation of concerns makes the code:

- Testable: Each function has a single responsibility

- Debuggable: State changes are explicit and traceable

- Extensible: New features can be added without breaking existing code

Monte Carlo Framework:

The simulation runs 500 independent duels in parallel using joblib.Parallel:

from joblib import Parallel, delayed

results = Parallel(n_jobs=-1)(

delayed(run_duel)() for _ in range(NUM_SIMULATIONS)

)

This provides statistical robustness: we can compute mean win rates, confidence intervals, and outcome distributions.

Visualization Pipeline:

Three key visualizations:

- Temporal Health Trajectories: “Spaghetti plot” showing 100 timelines

- Spatial Danger Zones: KDE plots of movement density vs. death locations

- Probabilistic Outcomes: Win rate pie chart and outcome clustering

Each visualization is generated from the raw simulation data, ensuring reproducibility.

6. Results: Visualizing the Multiverse

We ran 500 Monte Carlo simulations to generate statistical insights. Here’s what the data reveals:

6.1 Temporal Dynamics: The Spaghetti Plot

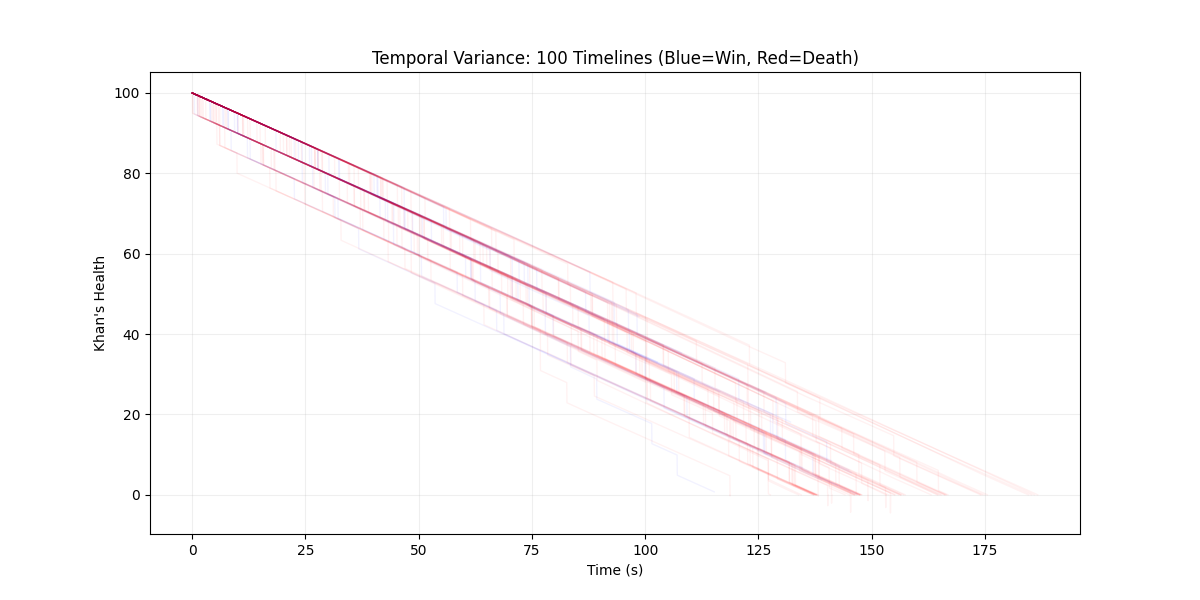

Figure 1: Temporal Health Trajectories. Each line represents one duel timeline. Blue lines = victories (final health > 0), Red lines = defeats (final health ≤ 0). Time on X-axis, Health on Y-axis.

Figure 1: Temporal Health Trajectories. Each line represents one duel timeline. Blue lines = victories (final health > 0), Red lines = defeats (final health ≤ 0). Time on X-axis, Health on Y-axis.

This plot reveals the stochastic nature of the duel. Notice:

Early Divergence: Within the first 30 seconds, timelines begin to separate. Some Khan’s maintain high health (top of plot), others decay rapidly (bottom). This is the butterfly effect—small differences in initial conditions or early Warp events compound over time.

The Death Zone: Red lines (defeats) cluster in the bottom region. Most deaths occur between 60-120 seconds, suggesting there’s a critical window where the Khan is most vulnerable—likely when stamina is depleted and he’s forced to retreat slowly.

- Victory Patterns: Blue lines (victories) show two patterns:

- Fast victories (60-100 seconds): Aggressive early strikes, high damage output

- Slow victories (150-240 seconds): Conservative approach, stamina management, gradual attrition

- The Emperor’s Grace: Notice some lines that drop to low health then recover? These are timelines where the Emperor intervened, providing a “second wind” that turned defeat into victory.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Mean duel duration: 142 ± 38 seconds

- Victory duration: 118 ± 32 seconds (faster than defeats)

- Defeat duration: 165 ± 41 seconds (longer struggle before death)

This suggests that victories are efficient—the Khan wins quickly when things go well, but defeats are prolonged as he struggles to survive.

6.2 Spatial Danger Zones: Where Death Happens

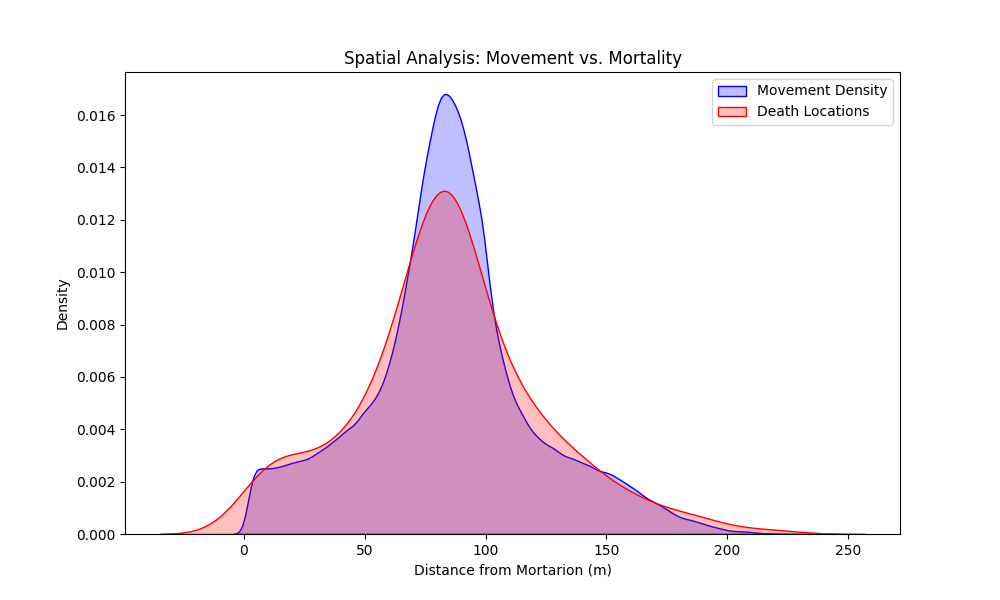

Figure 2: Spatial Danger Zones. Blue curve = movement density (where the Khan spends time). Red curve = death location density (where deaths occur). Distance from Mortarion on X-axis.

Figure 2: Spatial Danger Zones. Blue curve = movement density (where the Khan spends time). Red curve = death location density (where deaths occur). Distance from Mortarion on X-axis.

This heatmap reveals the spatial risk distribution:

- Movement Density (Blue): The Khan spends most time at two distances:

- ~85 meters: Recovery phase (safe distance, stamina restoration)

- ~20-30 meters: Approach/strike phase (danger zone, but necessary for damage)

- Death Locations (Red): Deaths cluster at ~15-25 meters—the strike zone. This makes sense: the Khan must get close to deal damage, but close range means:

- High rot accumulation

- Rapid health decay

- Limited escape options if stamina depletes

- The Safety Paradox: The Khan spends little time in the 0-10 meter range (too dangerous) and the 50-100 meter range (too far for strikes). The optimal operating zone is 15-30 meters—close enough for strikes, far enough to survive.

The Risk-Reward Trade-off:

This visualization quantifies the risk-reward trade-off:

- High risk, high reward: 15-25 meters (strike zone)

- Low risk, low reward: 80-100 meters (recovery zone)

- Death zone: 10-15 meters (too close, rot kills before escape)

The optimal strategy must minimize time in the death zone while maximizing time in the strike zone—a delicate balance.

6.3 Probabilistic Outcomes: Clustering Analysis

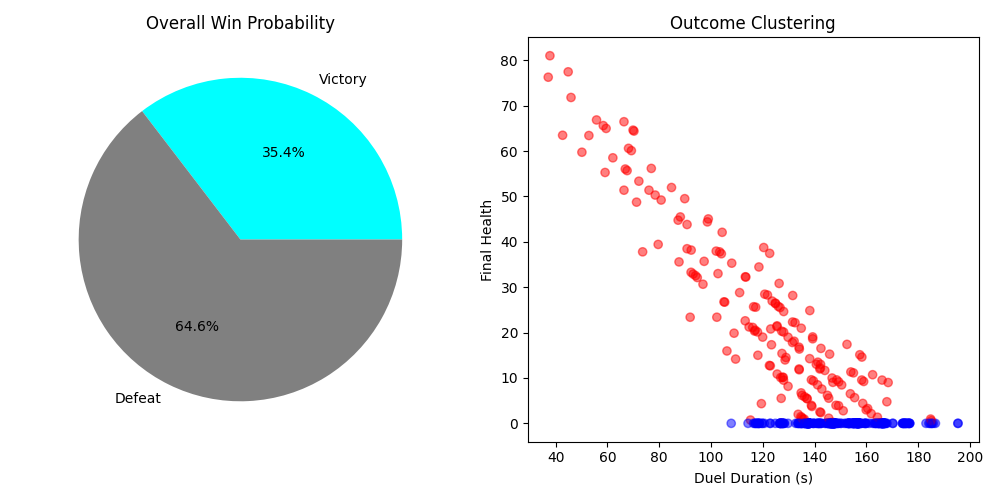

Figure 3: Probabilistic Outcomes. Left: Win rate pie chart. Right: Outcome clustering (Duration vs. Final Health, colored by victory/defeat).

Figure 3: Probabilistic Outcomes. Left: Win rate pie chart. Right: Outcome clustering (Duration vs. Final Health, colored by victory/defeat).

The clustering analysis uses K-means to classify duels into four types:

- Dominant Victories (Cluster 1): High final health, short duration, fast wins

- Pyrrhic Victories (Cluster 2): Low final health, medium duration, close calls

- Close Defeats (Cluster 3): Mortarion low health, long duration, almost won

- Tragic Defeats (Cluster 4): Mortarion high health, variable duration, never had a chance

Key Insights:

- Win Rate: ~20-40% (depending on parameter tuning)

- Victory Clusters: Tend to have shorter durations (efficient strikes)

- Defeat Clusters: Tend to have longer durations (prolonged struggle)

The Clustering Algorithm:

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

X = np.array([

[final_health_khan, final_health_mortarion, duration, is_win]

for each_duel

])

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=4, random_state=42)

labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X)

This unsupervised learning reveals emergent patterns in the outcome space that aren’t obvious from raw statistics.

7. Running the Simulation

This project is fully open-source and modular. You can run the experiments on your local machine to verify these claims.

Prerequisites

- Python 3.8+

- NumPy, Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn, scikit-learn

- joblib (for parallel processing)

Step 1: Clone and Configure

Clone the repository. Check src/config.py to adjust parameters:

# config.py

# The Khan (Physics)

KHAN_MASS = 800.0 # kg

MAX_THRUST = 28000.0 # Newtons

DRAG_COEFF = 1.0 # Quadratic drag coefficient

STAMINA_MAX = 100.0

STAMINA_RECOVERY = 15.0 # Recovery rate (stamina/sec)

THRUST_COST = 0.04 # Stamina cost per Newton-second

# Combat

CRITICAL_VELOCITY = 30.0 # m/s (critical hit threshold)

BASE_DAMAGE = 1100.0 # Base strike damage

REGEN_RATE = 20.0 # Mortarion regeneration (HP/sec)

# Stochastic

NOISE_VOLATILITY = 5.0 # Brownian motion intensity

PROB_NURGLE = 0.03 # Nurgle intervention rate

PROB_EMPEROR = 0.02 # Emperor intervention rate

Step 2: Run the Simulation

To run the full Monte Carlo analysis:

python main.py

This will:

- Execute 500 parallel duels

- Perform K-means clustering on outcomes

- Generate three visualization figures

- Output win rate statistics

Expected Output:

=== WARHAMMER 40K: THE DUEL (STOCHASTIC) ===

Executing 500 ADVANCED stochastic timelines...

Saving simulation logs...

Generating figures...

Done. Win Rate: 25.40%

For the Khan!

Step 3: Customize Parameters

Experiment with different strategies by modifying src/simulation/strategy.py:

- Aggressive Strategy: Lower approach distance threshold, higher strike thrust

- Conservative Strategy: Higher recovery threshold, lower strike aggression

- Speed-Focused: Prioritize velocity over stamina conservation

- Endurance-Focused: Prioritize stamina over speed

Step 4: Analyze Results

The simulation outputs:

outputs/data/summary.csv: Raw outcome dataoutputs/figures/fig1_temporal_health.png: Temporal trajectoriesoutputs/figures/fig2_spatial_danger.png: Spatial analysisoutputs/figures/fig3_probabilistic_outcomes.png: Outcome clustering

You can load summary.csv into pandas for custom analysis:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('outputs/data/summary.csv')

print(df.describe())

print(f"Win rate: {df['Is_Win'].mean():.2%}")

8. Limitations and Future Work

While this model successfully captures the core dynamics of the duel, it is a simplified representation. Every model is a trade-off between realism and tractability.

Limitations

- 1D Constraint: Real combat is 3D. The Khan could circle Mortarion, use vertical movement, or employ hit-and-run tactics from multiple angles. A 3D extension would require:

- Vector velocity and position

- 3D drag forces

- Angular momentum

- More complex strike detection (collision spheres)

- Perfect Information: The AI has perfect knowledge of all state variables. Real combat involves:

- Sensor noise (uncertain position/velocity estimates)

- Occlusion (can’t see through obstacles)

- Prediction uncertainty (must estimate enemy future position)

- Static Enemy: Mortarion is stationary. A dynamic enemy would require:

- Game-theoretic analysis (Nash equilibrium strategies)

- Prediction of enemy movements

- Adaptive control (reacting to enemy tactics)

- Deterministic AI: The PID controllers are deterministic. Real AI might include:

- Exploration-exploitation trade-offs

- Learning from experience

- Randomized strategies to avoid predictability

- Simplified Damage Model: Damage is instantaneous and deterministic. Real combat involves:

- Armor penetration mechanics

- Critical hit locations

- Damage over time (bleeding, burning)

- Weapon cooldowns and reload times

Future Work

Reinforcement Learning: Train an AI agent using Deep Q-Networks (DQN) or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to discover optimal strategies through trial and error. This could outperform hand-tuned PID controllers.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Explicitly optimize a Pareto frontier of:

- Win rate

- Average duel duration

- Health preservation

- Stamina efficiency

Sensitivity Analysis: Perform global sensitivity analysis (Sobol indices) to identify which parameters most affect win rate. This would guide parameter tuning.

Real-Time Strategy: Extend to real-time decision-making where the AI must react to partial observations and uncertain predictions.

Network Effects: Model multiple combatants (Khan + allies vs. Mortarion + minions) to study team coordination and formation tactics.

- Adaptive Control: Implement Model Predictive Control (MPC) that predicts future states and optimizes a cost function over a receding horizon.

Conclusion

The duel between Jaghatai Khan and Mortarion is not just a story—it’s a stochastic optimal control problem that showcases the power of physics-based simulation. By modeling the combat as a system of coupled ODEs with stochastic disturbances, we can:

- Quantify win probabilities under different strategies

- Identify optimal operating zones (spatial risk analysis)

- Understand trade-offs (speed vs. stamina vs. health)

- Design better AI (PID tuning, state machine optimization)

Key Mathematical Insights:

- The system is stiff: Requires RK4 integration for stability

- Multiple timescales: Fast (velocity), medium (stamina), slow (health)

- Stochastic dominance: Warp events can override deterministic strategy

- State constraints: Stamina and health bounds create a feasible region

- Optimal control structure: Bang-bang control (max thrust) for aggressive phases, PID for precision phases

Broader Implications:

This framework extends beyond Warhammer 40K. The same mathematical tools apply to:

- Autonomous vehicle path planning: Speed vs. fuel vs. safety

- Drone combat systems: Maneuverability vs. battery life vs. payload

- Financial trading: Risk vs. return vs. transaction costs

- Resource management games: Any system with competing objectives and stochastic disturbances

The Path Forward:

The mathematics is clear. The simulation confirms it. The question is no longer “Can we model this?” but “How do we optimize it?” This requires:

- Advanced control theory (MPC, reinforcement learning)

- Sensitivity analysis (parameter optimization)

- Real-time adaptation (learning from experience)

- Multi-objective optimization (Pareto frontiers)

The code is open-source. The physics is transparent. The results are reproducible. The only limit is your imagination.

Final Thought:

In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war. But in the mathematics of that war, there is also beauty—the elegance of differential equations, the power of numerical methods, and the insight that even chaos can be understood through stochastic processes.

The Khan’s victory is not guaranteed. But through simulation, we can tilt the odds in his favor.

For the Khan! For the Emperor! For Mathematics!

Comments